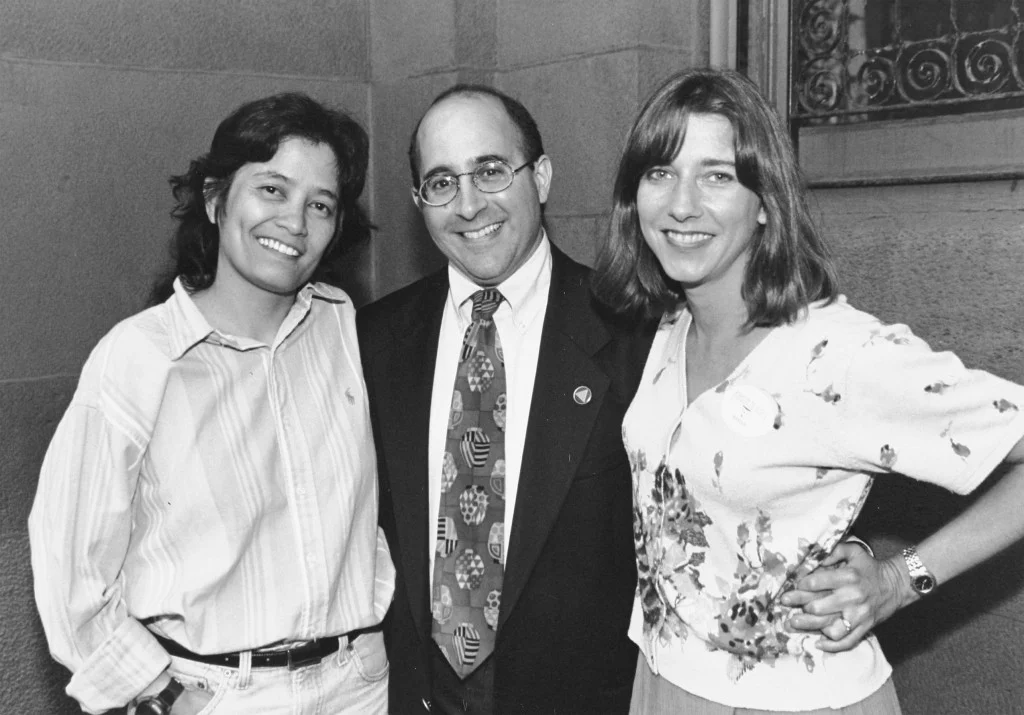

In the mid-1990s, a lawyer named Kathryn Lehman helped write the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which then easily passed into law and stood in the way of nationwide marriage equality for nearly two decades.

At the time, she was working for Congressman Henry Hyde, who insisted that same-sex couples demeaned the institution of marriage. But although it wasn’t common knowledge at the time, Hyde had secretly cheated on his wife. And Lehman was about to marry a man, despite being a lesbian.

The opponents of equality didn’t just have bizarre ideas about gays being immoral or curable. They had deep personal conflicts when it came to their own relationships, to the point that they carried on affairs and used straight weddings to cover their homosexuality.

When it came to defending marriage, the inmates were running the asylum. How could so many people have been so wrong? And what finally convinced Lehman to come out of the closet, put heterosexuality behind her, and start working to undo the damage she’d done years earlier by writing DOMA?

Music:

In Your Arms Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/